Humans and animals in refugee camps, past and present

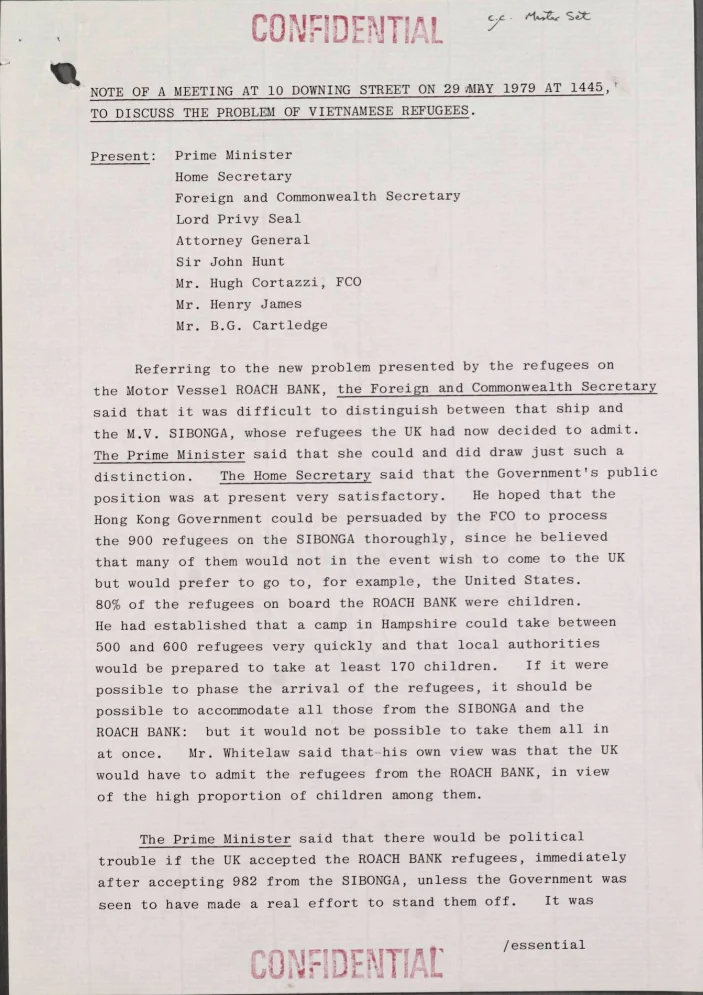

Title Image: Caged birds for sale in Azraq camp, Jordan, November 2016

Photo: Ann-Christin Wagner (University of Edinburgh)

On a showery day in October 1918, at the Baquba refugee camp northeast of Baghdad, a British officer noted the arrival of a marching party of refugees: two hundred people, and two hundred and fifty animals.

The sight wouldn’t have been unusual for him. The camp had been set up a few months earlier, and by October it was well on the way to reaching its peak human population of nearly 50,000 people. There were also thousands of animals there: six thousand larger animals (horses, ponies, and cattle), as well as seven or eight thousand sheep and goats by the end of 1918—and the number of animals would keep growing over the next two years, even as the humans were being moved on. In a recent article for the Journal of Refugee Studies I explore the different roles animals played in the camp, and in the lives of the people who lived there. It’s a history that has plenty of resonances with refugees’ lives today, as I explain below.

There were three groups of refugees at Baquba, each numbering a bit over 15,000 people and all Christians displaced from eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus during the first world war. The first were Assyrian Christians from the Hakkari mountains (today on the border between Turkey and Iraq), semi-nomadic pastoralists who had brought a large proportion of the camp’s animals. The second were Ottoman Armenians who had escaped the genocide, and the third were settled Assyrians from the towns and villages around Lake Urmia in the Persian Caucasus. In the summer of 1918, all were moving south into Persia, where they encountered British imperial troops pushing north from Mesopotamia (modern Iraq). The British began to funnel them into their own occupation zone, and chose the site at Baquba to accommodate them.

Plan of Refugee Camp Baqubah’, frontispiece to H.H. Austin’s book about the camp. The rectangles numbered 1–32 each accommodated roughly 1,250 refugees. West is (roughly) at the top of the plan. Of the crossed arrows, one points north and the other shows the direction of the prevailing wind.

The choice of site was dictated by the need to accommodate not just tens of thousands of people, but also the thousands of animals they had brought with them. At Baquba, a broad loop in the river Diyala created a site 1km across and 1.5km deep, which could then extend further west into an area bounded by two canals. The British military railway north from Baghdad could supply the camp, while the river gave a measure of security, and with the canals provided water for drinking and washing. There was an animal enclosure and a segregation paddock where sick animals could be kept isolated—rather like the isolation units for sick people where the camp authorities tried to control a medical situation that was at first little short of catastrophic. One serious problem was typhus, carried by lice: fumigation and disinfection were used to eliminate these tiny animals from the refugees’ bodies and possessions before they entered the camp.

In the camp’s first few months of existence, rations and other supplies were transported within it by 120 animal carts belonging to refugees as well as the mule-drawn carts of the British military. Once a light rail system had replaced these, plenty of work remained for the refugees’ animals inside and outside the camp. The British tried to promote economic activity among the refugees to encourage self-sufficiency. Animals, especially the refugees’ own animal, were crucial. The refugees’ flocks were a source of milk and other dairy products, and the British encouraged them to sell these in the camp and in surrounding villages—though grazing the flocks created ever more friction between the refugee herdsmen and local farmers trying to protect their crops from hungry sheep and coats. Many of the refugees earned cash wages, meanwhile: several thousand women and children worked inside the camp producing blankets and yarn for the American Persian Relief Commission (possibly using wool and feathers from their own sheep, goats, and hens), while men regularly did contract work outside the camp in labour parties that could number as many as 2,500 men and 1,000 oxen. Animal labour, and the refugees’ animal expertise, were an important part of the camp’s economic potential. The British themselves set up five poultry farms and a piggery in the camp.

The first commandant of the camp, Brigadier-General H.H. Austin, lyrically described the scene when the Hakkari Assyrian men and boys brought the flocks back from the day’s grazing. The women and girls would milk them, while also feeding the kids and lambs that had been left behind:

“The women and girls were extraordinarily dexterous and quick… and the men, too, evidently knew each mother and its own particular lamb or kid, despite the numbers, with unfailing certainty.... Both men and women would frequently bestow resounding kisses on the muzzles of the milch animals and their offspring throughout the proceeding, and a holy calm would temporarily descend upon the scene when each mother and child were united again.”

The refugees clearly saw their animals as more than just economic resources. But scenes like this one, which comes from a short book Austin wrote about the camp as soon as he returned to Britain, also hint at the role animals play in representations of refugees. Austin’s book very much concentrates on the Hakkari Assyrians, though they were only about a third of the camp’s population. That’s partly because he wanted to create a positive image of the refugees as a beleaguered Christian population. In the British imperial discourse of the time, educated urban populations in the Middle East were viewed as prone to nationalism and revolutionary politics. Depicting the Hakkari Assyrians as simple shepherds, who gave up their own blankets to keep their young animals warm at night, allowed Austin to create an image (with a biblical colouring) of a much more docile population. It was harder to present the Armenian or Urmia Assyrian refugees in the camp in this light: these groups were less amenable to British imperial strategy.

Meanwhile, the British were making plans to close the camp—which involved assembling and caring for yet more animals. Mules, oxen and other large animals were needed to transport the refugees and their belongings, and pull the ploughs that would allow them to be resettled more durably elsewhere. By 1920, when the British military occupation was giving way to a colonial administration in what had now become Iraq, the camp’s director was keeping careful records of the number and condition of its animals. Many thousands of refugees had already moved on by then, but the animal population remained high. Another 1,500 large animals, mostly mules intended for transport, were brought to the camp in April 1920 alone. Most of the remaining refugees were Hakkari Assyrian. In summer 1920, an effort to move them away was interrupted by the outbreak of a widespread revolt against British colonial rule. And at this point, another aspect of the refugees’ animal expertise became important: a military one.

The refugees, particularly the Hakkari Assyrians, were already unpopular with the local population. They were outsiders who had arrived in the midst of war, occupation, and hardship. They benefited from enormously disproportionate assistance from the British. Their flocks competed for grazing and ate local farmers’ crops. All of these were issues that might have been resolved with time, but when the British found themselves losing control in August 1920 they took a decision that permanently poisoned refugee/host relations: they used armed and mounted refugees as irregular troops to terrorize the local population. The camp director reported admiringly that armed refugees had burned down four nearby villages in one morning.

The British had always been aware of the military potential of the refugees and their animals. As early as summer 1918 they had formed some of them into a semi-regular force, the ‘Assyrian contingent’, to protect the marching parties travelling to Baquba—this included 800 ponies. British plans to resettle the Hakkari Assyrians had always involved arming them, ostensibly for self-protection. But after the 1920 revolt those plans changed, and they were incorporated permanently into the British armed forces in Iraq as the ‘Assyrian Levies’, a kind of militarized riot police that served throughout the 1920s as the iron fist of colonial repression. This set the stage for conflict, massacre, and renewed displacement when Iraq became independent in the 1930s.

A hundred years later, these events may seem like ancient history. But animals continue to play important roles in refugees’ lives, especially in camps. They can shape the space of the camp itself: animal markets and ‘goat barns’ are a distinctive architectural feature of Sahrawi camps in Algeria. Livestock or working animals can be economically and culturally vital in the life of a camp, as camels are at Dadaab in Kenya. Domestic animals can help make a shelter feel more like a home: in Azraq camp in Jordan, caged birds are sold at a cost equivalent to what a Syrian living there could earn in three or four days as an ‘incentive worker’ for a humanitarian agency. Displaced people’s interactions with wild animals can create dangers for both—we’ve seen this recently in the semi-formal settlements for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, which have brought displaced people into conflict with elephants. Animals can figure in outsiders’ representations of refugee camps, as when rats feature as a shorthand for squalor in journalists’ descriptions of them. Refugees themselves may say they are being treated ‘like animals’ when they are put in camps.

Caged birds for sale in Azraq camp, Jordan, November 2016

Photo: Ann-Christin Wagner (University of Edinburgh)

But so far there hasn’t been much academic research on animals in displacement, even when the animals are absolutely crucial to the livelihoods of displaced people. My research on Baquba also turned into a project with a more contemporary focus, funded by a seed award from the Wellcome Trust, which aims to change that. With practitioners from organizations including the UN refugee agency and Vets Without Borders, an interdisciplinary team of researchers, we’ve just published a 16-page special feature in Forced Migration Review that sets out some of the ways in which animals matter in the lives of refugees, and suggests avenues for future research. You can read it online here and download it as a PDF here.